by Bruce E. Parry

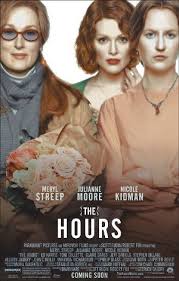

What a story! Actually it’s three, one-day stories: Virginia Woolf in 1923 (with some events in 1941), the Browns in 1951, and Clarissa Vaughan in 2001. Each has characters who are truthful to a fault, mixed with characters who are just living life. The truth that comes out is difficult, but important.

What a story! Actually it’s three, one-day stories: Virginia Woolf in 1923 (with some events in 1941), the Browns in 1951, and Clarissa Vaughan in 2001. Each has characters who are truthful to a fault, mixed with characters who are just living life. The truth that comes out is difficult, but important.

In short, this is not a light film. And there is a lot of depression in it in each age. But the characters debate the reality of life, the reality of death and the meaning of the hours spent just living life between the events that seem to define us (hence, the name of the film). Also, it turns out that The Hours was the working title Woolf used for her novel, Mrs. Dalloway.

Apparently, Virginia Woolf was quite depressive for much of her life. The snippets we are shown deal with her writing Mrs. Dalloway—which I confess I have never read—and her suicide (in 1941). I gather from the film that the third story of the film—that of Clarissa Vaughan—is actually the story of Mrs. Dalloway. It isn’t subtle. Clarissa (Meryl Streep) has a friend, poet Richard (Ed Harris), who is dying of AIDS. He has called her Mrs. Dalloway for just about their entire adult life. Not coincidently, in the novel, Mrs. Dalloway’s first name is Clarissa. Vaughan’s opening line in the movie is the opening line of the novel and we learn from Virginia Woolf (Nicole Kidman) that instead of killing Mrs. Dalloway, she kills of the poet, the visionary. She does it so the others would know the value of life. Of course, Richard dies.

Richard is brutally honest. He wants to capture every aspect of every moment and its history. That, of course, is an impossible task, but he has labored over ten years to produce a novel that does just that. It is proclaimed by all the characters in the film to be a “difficult” read. We, as viewers, of course, don’t get to read his novel.

The interplay between Richard and Clarissa is tense. While dying and depressed, he is brutally honest with her and points out that she has stayed alive basically to take care of him and he has stayed alive basically because he doesn’t want to disappoint her. That statement really gets to her and she wonders if her life isn’t somehow “trivial.” She makes the unfortunate mistake of saying this to her daughter (Julia, played by Clare Danes), who of course, is the most un-trivial thing in her life. Clarissa also has a lover, Sally (Allison Janney). Her relationships with these two are anything but trivial., We all get in funks like that sometimes, but it’s important to remember that we all have relationships that are important and hardly trivial.

The second vignette is of the Brown’s in 1951. The father (John C. Reilly) is an absurdly happy, World War II vet who is oblivious to the depression his wife, Laura (Julianne Moore), is suffering. Of course, she keeps it carefully hidden from him, but not from her son, Richy, who turns out to be the poet Richard in the third vignette. She, too, is reading and living out the novel, Mrs. Dalloway. She contemplates suicide, but is in the fifth month of her pregnancy with Richy’s younger sister. She decides against dying, instead making a devastating decision that is only revealed at the end of the movie. But—and this is the important point of the movie—she has opted for life.

The story of Virginia Woolf is also interesting. She, too, is a visionary who is brutally honest, but depressed. She has been moved by her husband Leonard (Stephen Dillane) and the doctors to a small British town of Richmond—from London—to make her life more “peaceful.” Of course, Richmond is killing her; she craves life in London. Her sister visits, but Virginia is deeply ensconced in Mrs. Dalloway and trying to decide whether to kill off her heroine or not. Her relationship with her husband is explored, for he’s the one trying to care for her, but isn’t listening to her. It’s clear that she never gets to move back to London; her death occurs while she is still residing in Richmond.

This is the kind of film I like to watch multiple times because it explores life from an emotional angle and really probes the basis for those emotions. This is not a light film. It really gets into the meaning of life and relationships, and while that sounds trite, the film is not. I’ve suffered from depression. Some say that depressives have a more realistic view of life. I don’t subscribe to that, but I believe the film uses that approach to confront both the other characters and the viewers. It forces us to make think about who we are. Much of the film is about what we look at and value, such as when Clarissa Vaughan is seeing her life as trivial, but ignoring the existence of her daughter and her relationship to Sally.

All in all, the film was duly recognized with Oscars and many other awards. Nicole Kidman got the Oscar for Best Actress and the film was nominated for another eight Oscars. It won two Golden Globes out of seven nominations. I think it is a film that has and will stand the test of time. Whether viewers will let its honesty stand the test of time is another question.

Copyright Bruce E. Parry

dible pace. There is an extravaganza of a song and dance scene where the Moulin Rouge is presented to us. The action is unrelenting for almost 20 minutes. A narcoleptic Argentinian falls through the ceiling; a midget dressed as a nun pops up; we’re taken to the Moulin Rouge itself, where the Can-Can is the order of the day. The dance scenes are reminiscent of

dible pace. There is an extravaganza of a song and dance scene where the Moulin Rouge is presented to us. The action is unrelenting for almost 20 minutes. A narcoleptic Argentinian falls through the ceiling; a midget dressed as a nun pops up; we’re taken to the Moulin Rouge itself, where the Can-Can is the order of the day. The dance scenes are reminiscent of